I put all my hopes into Stanford, and now, I wasn’t even sure if I’d ever get there.

We were stuck at the Denver airport -- my mother, grandmother, and me. We left my hometown of Omaha, Nebraska, for Stanford’s junior day football camp. This was my one shot at getting Stanford’s attention and a possible scholarship offer. But there was a delay and we missed our connecting flight to the Bay Area. And then we missed another one.

The camp was the next day and I was starting to panic.

I called Stanford and said, “I don’t know if I’m going to make it.”

It’s a helpless feeling, sitting in an empty airport in the middle of the night. There was so much uncertainty, but there was one truth: The next couple of days would be the biggest of my life.

•••

Growing up in Omaha, I definitely was a big fish in a small pond. I had a lot of success in high school -- I won three state Class A wrestling championships at Millard West High and was an all-state defensive lineman in football. But it’s hard to gauge your ability when you’re going against 215-pound offensive linemen.

I sent film to schools all over the country. But those schools mostly said the same thing, “Yeah, your film looks pretty good and you can beat a lot of people pretty easily, but we don’t know how you stack up against top competition.”

It was clear that schools would need to see me in person. That meant we had to go to them. My dad, Paul Phillips, drove me to as many camps as possible within a day’s drive of Omaha -- Nebraska, Iowa, Iowa State, Kansas, Kansas State, Northwestern.

Each trip was a sacrifice. These camps cost about $300 a pop and my dad lost his job -- after 26 years -- when his company was bought out during my freshman year in high school. My parents had just built their dream house, a place they expected to remain the rest of their lives. But with the house came debt. With my dad’s job situation and my sister starting college, this was a tough situation for all of us.

Even with my mom’s home daycare center -- 10 kids running around our house before and after school -- by the time you accounted for the breakfast cereal and the after-school snacks and driving the kids, we were operating on not much of a gain.

My dad found another job and helped that company reach close to maximum capacity in sales, but that success allowed for little additional growth and he again was laid off, because the company could no longer afford his salary. That was my senior year. My parents had to give up their dream house.

They tried to shelter me as much as they could, because they knew that sports were my life. It’s all I had, all my passions have been in athletics. They made sure to give me everything I needed -- the newest cleats, the new compression shorts, the cool Under Armour shirt -- just so I could look good, feel good, play good and not have to worry about anything. But I overheard conversations. I knew it wasn’t a good time.

One day, I sat with my mom and dad. They said, “Listen, we’ve done everything we can. We’ve done eight-hour car rides to wherever and back. We even drove to Wisconsin. But we can only fly you to one place -- your grandmother will put up the money for the trip. You choose.”

•••

•••

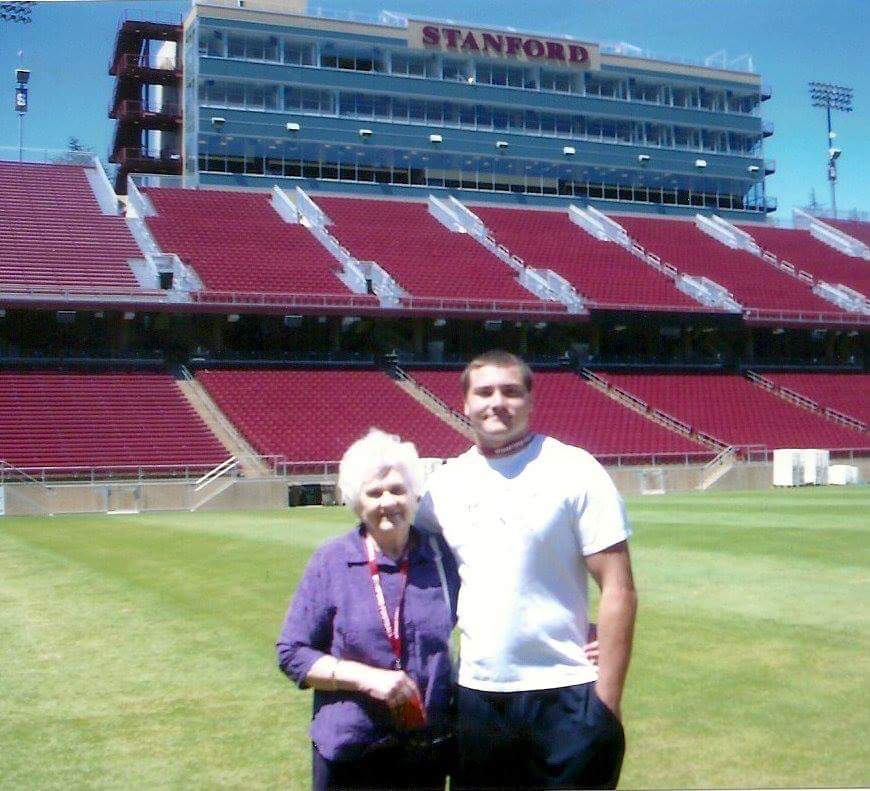

My grandmother’s nickname is “The Purple Lady.”

She lived on a farm with my grandpa in Wayne, Nebraska, about a two-hour drive from Omaha. Inside, everything’s purple. Purple, purple, purple, purple. And my mom is the “Purple Lady Jr.” This dream house that my parents built? The entire inside is purple. Every pot and pan we have is purple. If you come to my dorm room, you’ll see hand-me-down pots from my parents’ wedding that are purple.

You can figure, they loved Kansas State. We got Grandma K-State stuff just because it’s purple.

My grandparents, Don and Sandra Schultz, lived on a hillside with trees and a pasture down below. At the bottom was a pond where the chickens were, and a little playhouse that I was too scared to go into.

There was an outhouse, a bunch of broken-down cars. There are barns on the backside -- six of them -- and a bunch of stray cats. Grandma loved to feed the stray cats. Every morning, she’d call them, pour the milk and they’d run up and sit there. That’s probably why cats are one of my favorite animals.

I’m the only grandson in the family and she liked to spoil me. She’d buy all the girls princesses and Barbies, but she got to buy me boy stuff. She liked that. I was so rambunctious, my parents were sick of it, but she loved running around and trying to keep up with me.

We’d go there every Thanksgiving, every Christmas, every Easter. In the summer, I’d spend a week or two -- hunting, fishing, driving the four-wheeler, hanging out on the farm. I’d want to go with her to the garden, or to the chicken coop, to feed the cats or get the mail. Farm life was pretty cool.

My grandpa was a trucker his whole life. He lived crazy hours, not always eating right. Sitting in weird positions. He has diabetes. He’s blind in an eye. High blood pressure. He’s got everything wrong with him, but man, he is so funny. He’s a 5-year-old still. He’s just hilarious.

The weird dynamic is that because my grandpa was a truck driver, my grandma was the one who did a lot of the farming. My mom, Tammie, who is the oldest of three, said that when she was 11, she helped my grandma deliver a calf. She also helped deliver a foal. She was sitting there with Grandma, getting horse blood all over her, delivering a baby horse.

•••

I had never really heard of Stanford until my buddy’s brother wanted to go there. As soon as I found out what it was, I thought, Wow! This is everything I’ve ever wanted. I’m looking at schools with high academics and I wanted to play at the most competitive level.

I reached out as much as I could. Looked up the Stanford coaches, found them on Facebook or on Twitter and would message them every update I could.

I was a Texas fan. When Vince Young scored the winning touchdown in the BCS championship game to beat USC, that was the greatest moment of my life. I really, really wanted to go to Texas. But when I really thought about the one trip I would be able to take, I took my 17-year-old self and tried to mature up and see the future. It was no question: We’re going to go to Stanford. So, I got out the calendar, circled the date, called them immediately and said, “Hey listen, I’m gonna be there. So you better be ready.”

Grandma knew this was something I wanted more than anything. Farm life isn’t very lavish, so getting plane tickets for three of us was a sacrifice on her end. But when you’re in that position, I’m sure you’d do anything for your grandchildren. She made the conscious decision: I want to make Harrison’s dreams come true. I want to do everything I can to make his life the way he wants it. It was probably a no-brainer for her. She just had to nickel-and-dime a little bit to make it happen.

There was some guilt involved on my part. I had become close with Kansas State coach Bill Snyder. We’d talk for an hour at a time, often without even mentioning football.

When I left Kansas State the summer before my senior year, my family and I were sitting at a gas station right outside of Manhattan and I said, “I think this is going to be the place. I feel so bad about you guys having to buy me a plane ticket. What if I don’t get a scholarship at Stanford? What if we just lose that $3,000, for hotels and plane tickets? I’m happy here. These recruits are awesome. The coach loves me. I can play here. They’re a good team.”

But Grandma, not necessarily the most politically correct, would say, “You’re stupid if you’re not going to Stanford.” She wanted to help us come out. If she didn’t do that, I probably wouldn’t have ended up here. Maybe I would have said, “I don’t know guys, Stanford is such a big school. They’re so prestigious, I don’t want to waste your money and waste your time.”

Instead, we were on a plane to the Bay Area. Grandma saved the day.

•••

•••

I tried to sleep on the planes or in the airports, but I got maybe an hour and a half that night. We missed two connecting flights, and were redirected to Los Angeles from Denver. We got to the Bay Area at 5 a.m. in the morning and junior day started at 8:30.

We came straight here, super tired. We did all the tours, talked to all the coaches, did the weight room stuff, the cafeteria stuff, the dorm room stuff, went to the bookstore, Hoover Tower. By the time we were in the meeting to talk about some of the weight-room goals, I looked over and both my mom and grandma were head-bobbing.

We got on the field the next day, and that’s when I realized there are some very big people here -- a lot of 6-6, 330’s, big offensive linemen, big defensive linemen. When practice began, right off the bat we go into 1-on-1’s, then 9-on-7’s, then full-team. There was a lot of hard hitting. I definitely competed and didn’t look like a runt or anything like that, but I didn’t really wow anybody.

We got to the hotel at 8:30 and I immediately fell asleep -- for 12 hours. The next day was a long day of camp -- two sessions. And, as humbling as I can say, I really did dominate. Rep after rep after rep after rep, I put my heart and everything I had into each play.

They did a drill called King of the Boards, where all the offensive and defensive linemen line up across from each other with a board between your feet, about four yards long. On the whistle, you run and hit each other. Whoever pushed the person past the board was the winner. Winners stay, losers are done. Single elimination.

Coach Mike Bloomgren grabbed an offensive guy to demonstrate the drill. It was A.T. Hall. And Coach Randy Hart grabbed me. We were both guys they really had their eyes on. A.T. was 335 at the time. I was 240. We had a stalemate.

There were probably 150 offensive and defensive linemen. Do the math … we probably had 15 reps and I made my way to the finals. The other guy was about 275, big and country strong, and I ended up winning. I was the King of the Boards.

A couple of days later, I called Coach Shaw after we exchanged messages. He picks up, from Africa, where he was on a safari with his family.

“You said you were going to come and you were going to earn your scholarship,” he said. “And you did. I’m happy to tell you we’re offering you a full-ride scholarship to Stanford.”

I was sitting on the corner of my bed and just fell backward, full-eagle spread. I screamed, and laid there probably four or five seconds. Then I realized I was still on the phone. I sat back up and he was still talking. I remember saying, “Yes, yes, yes, yes,” and “thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you.” I pretty much told him, I’m coming.

I ran upstairs and told Mom and Dad. They both cried.

I called Grandma, and she cried too.

•••

•••

During camp before my sophomore year, I was named the starter at tackle. But in our first game at Northwestern, I tore my ACL. After Mom came out for the surgery, she got a call that Grandma had a stroke. Mom flew home, landed in Omaha at midnight, and drove straight to Wayne.

A couple of hours after Mom got there, Grandma passed away.

She was supposed to come see me play.

It’s kind of a crazy story -- she’s the reason I’m here. She always wanted to come out to California and she did it. She kept saying how beautiful it was and what a great decision it was.

Now, my grandpa is a big fan too. He loves going to get coffee in little smalltown Wayne, Nebraska, where people are always asking, “How’s your grandson?” Everywhere he goes in town, it’s the same thing. I think he loves that.

I’ve learned a lot about family through all this. My relationship with my dad for years was more of a leader-and-follower type of thing. I watched how he handled himself. There weren’t a lot of long talks and stuff like that. But, as I got older, and it seemed more of a reality that I might be leaving the state, we got closer. It was a sense of, Dad, I thought you would be around forever and I thought I’d always be able to talk to you if I ever needed something. Now, I might not be here.

He wanted to come to Stanford on that trip and I know it was tough for him not to, but he’s always wanted whatever was best for me. His biggest influence on me was hard work and work ethic, and I put that all into football.

My mom’s biggest impact on me is her heart. She’s always providing and caring for others and putting others before herself. The daycare she ran, having kids of all ages in the house … she definitely gave me a servant’s heart. I see my life as a combination of the two -- using hard work to help others.

With the platform I have as a Stanford football player, there are endless possibilities in the lives I can touch and that’s what I really want to do, to bring joy to people’s lives who may be struggling or need somebody to lean on.

My family, and especially my grandma, taught me that. They have influenced me in ways I never thought possible.

It’s a crazy cycle that happened. I’m a very religious person and a strong follower of Jesus, and I know that Grandma is definitely in a better place, that she’s cheering from above.

It gives me something a little extra to play for. I wouldn’t be where I am without her.

•••

Harrison Phillips